A couple days back I was trolling the dusty bins at a local record store when I came across a well-maintained copy of The Allman Brothers 1972 classic album, Eat a Peach. This is one of those records with a long backstory for me, and I didn’t think twice before adding it to my stack.

I first heard about The Allman Brothers from my Uncle Paul. When I was a boy my uncle lived in Texas, so before he moved back into our house in Michigan when I was 10-years old I’d only met him a few times in my life. Even though I knew little about him I always liked him: he is younger than my mom and her other siblings, and whenever I saw him he was usually willing to wrestle and knock me around, an appealing trait to a boy growing up in a house with two women and an older man.

When Uncle Paul moved into the house with my grandparents, my mother and me I, think he was pretty down on life. After all, how else would any reasonable person in their early 30’s feel about moving back in with their parents?

Life in Texas had been rough on Paul. He’d married, which had last but a short time before he divorced; he then—horror of horrors to my very white, Christian grandparents—lived with another woman. And not just any woman but a Mexican woman. That hadn’t worked out either. Paul had found work in construction hanging drywall; jobs were often inconsistent, and even though he was only in his early 30’s the physicality of the work, coupled with his regular drinking, were taking their toll on his body.

The head of the house Paul moved into was undoubtedly my grandfather, a man capable of great kindnesses but also one with definitive ideas about rules and their being followed. There were several taboos under grandpa’s roof, but Uncle Paul, whom I would soon learn had always been a bit of a rebel, wasted little time in toppling the four most sacred pillars: he drank alcohol, cheap cans of beer such as Bush and Bud Light that he kept cool on warm Michigan night by storing them in soft plastic koozies; he smoked cigarettes, Kools or some other brand of menthol; he cursed regularly, apparently unafraid of the forbidden and foul four lettered combinations; and on Sundays he didn’t go to church with the rest of us.

In retrospect I imagine Uncle Paul’s knowing and seemingly self-pleasing dismissal of house rules was an effort at self-assertion, of maintaining some sense of dignity and autonomy in the face of what I imagine must have been a difficult, if not outright humiliating, situation for him. I don’t know how he and my grandfather worked things out—my family is famously non-communicative and could out-silence a mime—but eventually they arrived at some form of detente, and we all kept quiet as Paul continued smoking, drinking, cursing and not going to church.

Uncle Paul was searching for a solution to his circumstances and it didn’t take long before he landed on a plan: he would join the Army. He had already served in the military after high-school—he’d been stationed on the DMZ in Korea—and apparently looked back on that time of structure, discipline and order with a newfound appreciation.

He went into town and talked to a recruiter, which is where the first of many missteps seems to have begun. It’s never been clear exactly what the recruiter promised Uncle Paul, or what Uncle Paul thought the recruiter had promised him, but the seeds of that misunderstanding would soon bear some bitter fruits.

In the interim Uncle Paul began preparing for the physical tests. He started an exercise regimen and tried to lay off the cigarettes and drink less. I still remember him excitedly bringing home a shiny new pair of Asics Gels, shoes in whose soles were located navy-blue patches of gooey gel that were supposed to do all sorts of magical things, like make you as fast as Carl Lewis and clear your lungs of tar.

He kept at his routine with a focus I’d never before seen in him, and after a couple weeks returned to the recruiting office were he leapt all the required hurdles. He’d made it, and excitedly he began preparations for his new life.

A few weeks later Uncle Paul shipped out for basic training in Fort Knox, Kentucky.

A few weeks later Uncle Paul was back in our house in Michigan.

It’s still unclear what the problems were. Remember, no one, and I literally mean zero people, actually communicate with one another in my family. From what I can piece together it seems there was a sizable gulf between what Paul heard the recruiter promise and what Paul found on the ground in Kentucky. And in the face of these shortcomings Uncle Paul had gone AWOL.

For those not familiar, AWOL means Absent With-Out Leave, and is a military designation to indicate that you’ve abandoned your post without permission. It’s a step before deserting, and not surprisingly, given their emphasis on discipline and following orders, going AWOL is not something the military branches take lightly. But Uncle Paul was a Ducat, which means that often he was dumbly stubborn, and despite his better sense he had simply walked out.

He hung about my grandparents’ house for a couple weeks, weighing his options and worrying that MP’s might arrive at any moment to arrest him. During this time my grandma wrote hurried, anxious letters to our state senators; I’ve never been able to determine what outcome she was hoping for, but she kept at it with the same resilience Paul showed during his exercise campaign.

Eventually, after conferring with former service-members, Paul returned to Kentucky, where he was summarily placed in an Army jail. After a week he was discharged.

This is what I knew of the man who introduced me to popular music, music which, up to that point in my life, I’d heard only in bits at school or friends’ houses. The main reason for this is that my grandparents were solid and stalwart supporters of a certain notion of the 1950’s, and seemed to believe that any music created after Elvis started looping those hips like a lasso was made of-, by-, through- and for- the Devil. I think they felt this way because as they watched both of their sons slowly slip and sink into the counter-cultural movement of the late 60’s/early 70’s it was far simpler to blame the Beatles for their sons’ waywardness than examine their parenting procedures.

Sadly, popular music wasn’t a void my mother was going to fill either. For her part my mother was, and in some ways still is, one of the more culturally illiterate people I’ve ever met. She was born into a crazy, at-times wonderful period: she was 18 when Woodstock happened, but little of it ever took hold. She was more inclined to keep her mind safely shaded indoors, afraid of the surrounding world that her parents had convinced her had so polluted her two brothers.

(Mom wasn’t all square, and in time she would topple the touchiest of taboos. Where my uncles pushed boundaries by smoking pot, getting drunk and catting about, my mom would one-up them all by getting pregnant and having me out of wedlock with a man none of the rest of my family had, and to this day still have never, met. Take that propriety!)

Back from his shortened stint in the military and with the last of the 80’s slipping past, Uncle Paul slowly introduced me to his favorite music: Bob Seger and the Silver Bullet Band, ZZ Top, and eventually The Allman Brothers Band. It was Uncle Paul who first told me about Eat a Peach, propagating the oft-repeated and cleverly appealing, though ultimately untrue, story of how the album received its name. [1]The urban legend is that the band named the album Eat a Peach after their founding member and guitar god Duane Allman crashed his motorcycle into a delivery truck carrying peaches. In actuality, the … Continue reading

It was Uncle Paul from whom I eventually obtained a copy of Eat a Peach. I stealthily flew the album into my grandparent’s house under their otherwise attentive radar. I think they knew what I was listening to, but by this point in time I think they were realizing that their long-standing battle against rock music was one they weren’t ever going to win.

(For some years Springsteen’s Born in the USA had been openly permitted in the house, largely because I believe my grandparents, not unlike President Reagan, honestly thought the song was patriotic, and not the satiric criticism a close listen will reveal. It wasn’t long until other bands began slipping past my grandparents’ bulwarks—at my next birthday my neighbor gave me Poison’s Open Up and Say Ah, whose preservation I wisely argued for by insisting that it was a gift, and as such it would be rude to throw it away; it wasn’t long after that a dubbed copy of Appetite for Destruction snuck into my room as well.)

For some time I listened to Eat a Peach in the quiet of my room, feeling warm and safe and not unlike how I imagine Brian Wilson once must have felt (The Beach Boys 22 Greatest Hits had made it into the rotation by that point as well). I played the music at low volume to avoid my grandparent’s ire, or plugged in headphones if it was late at night. Though I really enjoyed the album, sadly, as the years shifted, I lost track of the tape.

Several years later I started high-school, a Catholic prep affair outside of Detroit. Like many of my classmates freshman year was nerve-wracking: expectations for scholastic development ran high, and there was always the lingering fear that if you slacked off one of the Christian Brothers who ran the school would hit you (I only saw it happen once, but the threat of it hung like a specter throughout my tenure).

I was required to take a language and started French. The class was run by a wonderful caricature of a human, Mr. Evo Alberti. He was, as the name suggests, Italian, though like many educated Europeans he spoke several languages flawlessly. Mr. Alberti was a large garden-gnome of a man, with a prominent Roman nose that drooped below his drawbridge eyebrows like a counterweighted sandbag. To supplement his teaching income he ran a knife-sharpening business out of his basement called True-Hone; my senior year he gave the entire class black baseball caps with the company’s named printed on it in shining silver letters.

In class I sat behind a kid named Matt. He was the self-appointed class clown, always goofing off making fart noises and searching his dictionary to compose some of the most ridiculous lines ever uttered in the French language. I remember him getting into an argument and yelling at Mr. Alberti, Souchez-ma concombre, which roughly means, Suck my cucumber. Despite his burly exterior Mr. Alberti was a kind, older man and didn’t deserve this flip. He looked down, licked his thick buttery lips, shook his head and calmly told Matt to get out.

For whatever reasons French came reasonably easy to me and I did well in the class, an outcome it didn’t take Matt long to realize. A couple months in, as Mr. Alberti was talking with another boy across the room, Matt turned around and asked if he could cheat off me on that week’s exam. He’d been doing it already, looking back over his shoulder or under his armpit surreptitiously during previous exams. I was too scared to say Yes—as I said, Catholic school comes with certain historical expectations of punishment for engaging in just such things.

Despite my refusal Matt kept struggling and sneaking looks, pestering me to let him cheat. As his grades continued to slip Matt finally resorted to his coup de grâce—bribery. His proposition: For every test you let me cheat off you I’ll buy you an album.

This was too good a deal to pass up. I was 14, didn’t have any income and had no desire actually to get a job (you see, these trends had their claws in me at an early age). And so I relented. During the next test I wrote with my paper pressed so far forward on my desk that I was nearly writing on Matt’s test, and for the first time in his fledgling French career Matt actually passed an exam.

Though I’d become increasingly exposed to music over the years, after thinking about it I decided to request Eat a Peach. And Matt, like any good 14-yo who makes such a promise, refused to follow through on his end of the deal.

Every week there was a new excuse: I’m still trying to save money; I had to buy Christmas presents; It’s my brother’s birthday. As the weeks turned into months I gave up hope of ever receiving the tape. Matt kept cheating: he was a force I grew too tired to fight, and while I didn’t actively help him I certainly no longer tried to forbid him.

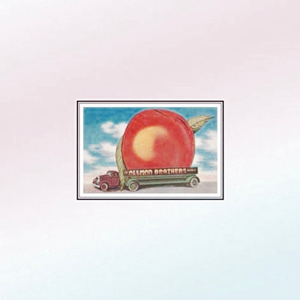

Then, as the school-year drew to a close, there appeared on my desk a wrapped rectangular package, 3″x4″x1″, compact and hard-cased. At home I ripped it open: there was that familiar cover with its soft blue-pink fade and the red-tractor truck hauling a large amber peach with a sun-spot shining on its side. Excitedly I played it a couple times—though most critics argue that Melissa is of greater worth, Blue Sky was and remains my all time favorite Allman Brothers song.

Eat a Peach didn’t stay in my rotation long: unfortunately for The Allman Brothers by that point a little thing called Grunge had happened, and my mind and ears had gone elsewhere.

References

| ↑1 | The urban legend is that the band named the album Eat a Peach after their founding member and guitar god Duane Allman crashed his motorcycle into a delivery truck carrying peaches. In actuality, the truck Duane Allman ran into was carrying a large construction crane. The album title comes from an interview Duane gave shortly before his death; when asked by the reporter how he was helping the revolution (I love reading about the 60’s/70’s: it’s so quaint that Boomers not only thought there was a revolution coming but believed themselves at its forefront), Duane replied, “I’m hitting a lick for peace. And every time I’m in Georgia I eat a peach for peace.” |

|---|