On January 6th, right wing insurgents stormed the Capitol building in Washington, D.C. The Times recorded some interesting reflections from a police officer who was on the scene:

They (the insurgents) went and did what others have only talked about. And it’s not just the right wing who are fired up. There must be millions of frustrated people who have no outlet for their pent-up feelings. And along comes this group, and they not only want to restore traditional values, but they try to do something about it. They tried to make a change, they really did. And that still has major appeal in this country.

It’s not about being on the right or left. Some of these people are probably just pissed off at their bosses. And normally you don’t do anything about those feelings, you know, you just hold them in. But when you see an act like this — well, it makes you wonder if others might go out and do the same.

Readers of this rag are intelligent, perceptive people, and at this point in the reading experience that will constitute this essay it’s likely that everything is checking out. After all: we all know insurgents did storm the Capitol on January 6th, and that quote sounds accurate enough. Only, it’s not entirely on point.1

The quote above is from a police officer reflecting upon an insurgency, and it was in the Times. But it’s taken from the November 29, 1970, paper, in a report on a Japanese coup attempt that occurred several days before. To contextualize things for our American readers: in late November, 1970, Nixon was president and I Think I Love You by the Partridge Family was on top of the pops; from this we can conclude that it was a less-than stellar time in the old US of A. Based upon the coup attempt, things weren’t going super smoothly over in Japan either. As far as the quote goes: I modernized the language and removed several Japanese-specific references, but the gist is consistent, and curious readers can compare it with the original here.2

INCIDENTS! INCIDENTS!

The coup attempt has come to be known as the Mishima Incident, after Yukio Mishima, the leader of the the undertaking. In general, any event that obtains the title of Incident is significant. If you hear there was an Incident, you’ll probably start thinking about a terror attack; airplanes colliding in midair; naval battles involving men in flouncy, colorful shirts; string cheese. This Incident, however, is a fumbling exception that proves the rule. If you were to convert the Mishima Incident into a movie, it would immediately become Dog Day Afternoon: another story in which absolutely nothing goes as planned, there’s some strange background sexual stuff going on, and the whole thing ends in terrible bloodshed.

On a lighter note, Incidents would be a great way to organize any ethnic restaurant’s menu: Starter Incident, Fish Incident, Noodle Incident, etc.

Mishima was a very famous and significant Japanese novelist, and if you’re wondering how famous and significant — simply note that he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature on multiple occasions. In other words — no slouch. In addition to his novels, short stories, poems and essays, Mishima was also an increasingly fervent right-wing nationalist who was frustrated with Japan’s diminished standing after WWII. He hated that the emperor had been weakened (specifically, he was no longer considered divine); he raged against the fact that Japan was prohibited from having a formal army; and he was appalled by the increasing Westernization of the country — although it’s worth noting that his growling rebukes didn’t always line up with his own lifestyle choices, because often that’s how life is in reality (though just as often — such a move would be a tough sell in a novel).

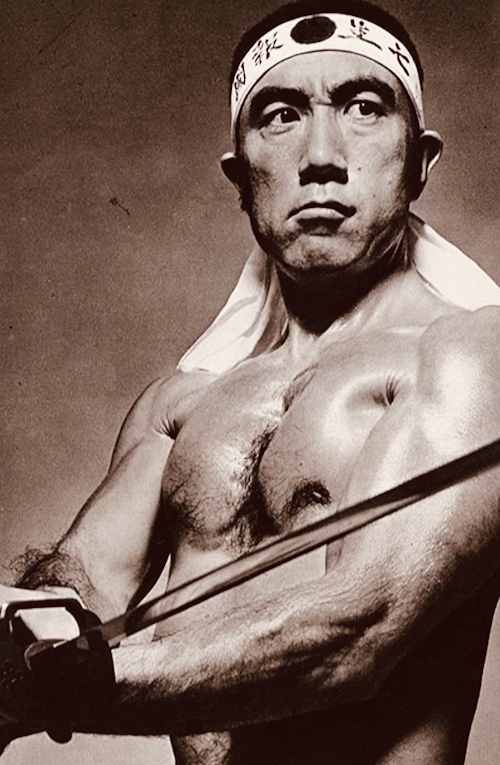

Other curiosities: to compensate for some body images issues Mishima became a competitive weight lifter and got totally jacked (seriously); trained with a Japanese civil defense group before forming his own private militia; briefly considered marrying a woman who subsequently became the Empress of Japan; then married another woman and had two children, all the while regularly visiting gay bars. Oh, don’t forget the multiple Nobel Prize nominations…

Mishima seems to have been the sort of person my grandfather would have called a real character.

What happened in Japan that day in late November is one helluva story, but before we tell it we ought to pause and look briefly at the concept of seppuku — which is a statement that no matter how long you lived, you could never write enough times.3

THE PART WHERE WE LOOK BRIEFLY AT THE CONCEPT OF SEPPUKU

Many of us Americans know seppuku as hari-kari, and if you’ve ever watched a samurai movie (or seen Airplane!), you probably have a basic idea of what’s involved. In short, seppuku is a form of ritual suicide that was developed in the 12th century by Japan’s samurai class. Like all things Japanese it’s highly ritualistic and ceremonial, is split by gender (women have their own processes and rituals), involves poetry, and appeals to concepts of honor that are highly foreign to modern American ears.

As for the act itself: it’s terribly concise. In fact, its concision makes it rather awkward, as if it should take more words to describe something this violently bizarre. But, as you’re about to see, it doesn’t. To commit seppuku a person drives a knife into their own stomach, then cuts across their abdomen to disembowel themselves before turning the knife sharply upward toward the torso. Lucky ones hit an artery and die quickly. As we all know that not everyone in life gets lucky — and to speed up what could become a terribly slow process — a second is typically on hand to decapitate the dying person.

Like corsets and high-wheeled bicycles, seppuku was largely out of favor by the early 1900’s, although it did have a brief flourishing at the end of WWII, when many Japanese troops chose to commit seppuku rather than surrender to the Allies. And it drew international attention when it was put into practice by Yukio Mishima in 1970.

THE PART WHERE WE COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Attentive readers that you are, it’s likely you’ve already figured out that the Mishima Incident was a total failure. More on that in a minute. What I’d like to focus on first are the many overlaps between Mishima and those folks who stormed the Capitol on January 6th.

Ultra-nationalists connected to groups espousing extremist ideas;

Highly militaristic, often having a background in the armed forces;

Frustrated with perceived weaknesses in the existing political leadership;

Upset about social and cultural changes that were moving away from traditional lifestyles, values and norms.

The humanists on staff would like to remind you that every person is a uniquely special lamb in the Lord’s beloved flock, etc., etc. Still, if you’ve watched the news since — oh, January 6th — I think you know exactly the sort of people we’re talking about. That applies both to those who stormed our Capitol and Yukio Mishima and his followers. But there’s one glaring difference between Mishima and our homegrown insurgents, and I think it’ll come clear if we learn a little more about the Mishima Incident.

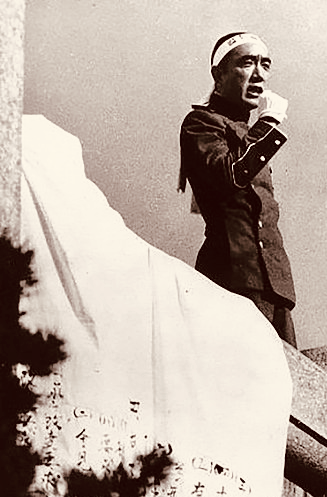

On November 25, 1970, Mishima and four members of his militia used pretenses to get inside a military base in Tokyo, where they captured the camp’s commander and barricaded themselves inside his office. Mishima stepped out onto the balcony to address the soldiers gathered below. He intended to wow them with a 35-minute speech, a rousing, nationalist oration whose logic and rhetorical flourishes would immediately cause a coup and re-establish life as it was pre-WWII. 7-minutes later, after being laughed at, jeered, booed heckled and otherwise disregarded, Mishima gave up and came back into the office. Ashamed, dejected, defeated and dishonored — it doesn’t take much to guess what Mishima did next. We’ll get to the gory ending of the Mishima Incident in a moment. First I’d like to complete the wobbly little circle I’ve been drawing linking Mishima to our January 6th-ers. Specifically, I would like to suggest that anyone who was involved in the insurgency on January 6th be required to commit seppuku. This being America, it’d be absurd to appeal the same sense of honor (or failure) that motivated Mishima to take his life; instead, we may have to help our insurgents toward this end by focusing on the one and only true American value: MONEY.

We’ll get to the gory ending of the Mishima Incident in a moment. First I’d like to complete the wobbly little circle I’ve been drawing linking Mishima to our January 6th-ers. Specifically, I would like to suggest that anyone who was involved in the insurgency on January 6th be required to commit seppuku. This being America, it’d be absurd to appeal the same sense of honor (or failure) that motivated Mishima to take his life; instead, we may have to help our insurgents toward this end by focusing on the one and only true American value: MONEY.

Think of the resources that have gone — and will continue going — toward researching, interviewing, investigating, arresting, prosecuting and ultimately jailing these insurrectionists. It’s worth clarifying that those resources are not abstract concepts. Literally (and I really do mean literally) that’s our money and our time; it’s our energy; it’s our psychic scars that are being left unresolved; our traumas that are proliferating like fungal spoors.

It’s true that we cannot bring back the five people who were killed in this Incident, and it’s debatable if a mass seppuku would actively heal anyone who was hurt on that day. It is beyond argument, however, that mass seppuku will save us immeasurable time, energy, money and other resources, each of which can be put toward something far more interesting and of greater social value than prosecuting the QAnon shaman.

This is the part of the essay where it’s easy to imagine someone countering with an appeal to morals. Though: Which Moral(s)?, turns out to be a surprisingly interesting question. On this subject the right has largely failed us (see: January 6. If that fails to convince, see: Trump, Donald J.) while the left has succeeded simply in being not the right (which, it should be noted, isn’t as challenging as it seems). The hitch in the moral giddy-up is finding a moral(s) that we as an American people actually believe in.

Might it be Justice? — Let’s run that concept up a non-white flagpole and see how it flops in the winds…

What about Truth? — Perhaps, but was that Fox’s or CNN’s truth, Tucker’s or Maddow’s?

Goodness?

Decency?

Fairness?

Beauty?

That last one’s a joke just to show us how far off the charts we’ve gotten simply by initiating this conversation. We can spin and spin the Wheel of Morals, but it never seems to stop on anything useful. All of which leads me to suggest the one moral that has guided our country since it was founded — Salability. By which I mean: Will it sell?? 4

I believe a mass seppuku will sell like hotcakes. Better than hotcakes, in fact, because hotcakes you can eat only once, while televised death — can be re-watched, and thus re-purchased and re-advertised to, an infinite amount of times. If you think I’m off my rocker — think of the amount of hours people spend dissecting one interception or plot shift on whatever PBS-meets-soft-porn Cable Channel series is presently popular. Those are just games and fictional TV shows and they have multi-billion dollar spin-offs!

Can you imagine how much money could be made selling the rights to Alex Jones’s seppuku?

Let me repeat that so you can really consider the question: Can you imagine how much money could be made selling the rights to Alex Jones’s seppuku?

And to all those prissy, squeamish, high-nosed tut-tuters — tell me you wouldn’t watch that! Look me in the pixellated eye and tell me you wouldn’t pay to watch Alex Jones read some terrible death haiku he wrote himself (!) then slash his guts out on live TV??

Sure, the logistics would be a challenge, but if the Weeknd could pull off that sprawlingly crazy Super Bowl show, we can definitely make this work. Short term: we round up everyone who was at the Capitol Carnival on January 6th (a task made much simpler by their predilections for social media sharing…) and relocate them to some nice pre-fab enclosures in Arizona: sure they’re rustic, but that’s part of their appeal. There they’ll await their turn in the rotation — like a baseball pitcher, only with less golfing. During this period they can enjoy a daily ration of water-like product (singular emphasized, not a typo), work on their tans, bask in the long desert sunsets, and learn the rigorous complexity of traditional haiku formulations. Every now and then — and it will be random and intermittent, like good rewards/punishments ought to be — one of them will be called upon commit seppuku. And we — all of us, here in America and across the globe — will watch. Oh god how we’ll watch.

THE END OF THE INCIDENT

You’ve already guessed what happened to Mishima, but I promised you Dog Day Afternoon, and well — it’s time to deliver. (If the Alex Jones thing made you squirm, you may not enjoy this next portion.)

Upon returning from his failed insurrection speech, Mishima apologized to the camp director who had been tied up. (This is that whole honor thing that we here in America — just don’t get. At all.) He then committed seppuku by ramming a knife into his stomach. One of his gang — a man named Morita, who was most likely also Mishima’s lover — had been named as his second, which, if you’ll remember, means he was supposed to decapitate Mishima after Mishima had cut open his gut. Well: Morita tried. Three times. And failed. All three times. I don’t mean that he couldn’t wield his sword. I mean that he failed to decapitate Mishima over three separate attempts. Finally, another member of the militia — Mr. Hiroyasu Koga (there were two Mr. Kogas in this group: honestly, 40% of the people who stormed this building were Kogas, but only one was trained in swordsmanship) — grabbed the sword and cut off Mishima’s head.

It gets worse.

Morita then decided that he, too, needed to commit seppuku, for he couldn’t let Mishima die alone… Remember that they were probably lovers, which honestly makes all my relationships look as if they were constructed from masking tape and a leftover stick of flavorless Doublemint: and I do mean all, because honestly I wouldn’t do this for my mother, and she birthed me! So Morita committed seppuku, and when he was finished — Mr. Koga cut off his head as well.

Mishima’s corpse was returned to his family the next day. But not before his head was reattached to his body and slathered in makeup so that he didn’t look — you know — decapitated.

As for the Kogas — they went to jail for a couple years. And then they were released. We’re talking jail sentences of around three years here. Three, as in the number after two but before four! After which life, as it’s inclined to do, just kept moving on. And a man who participated in a failed coup and decapitated two human beings blended without incident into the light blurring off a skyscraper while the sun set over Tokyo.

- When writing a post about seppuku you’ll find endless metaphors sharpen their teeth and cry out from between expectant lips, which is part of why this post is named after a great song by Meatloaf. While I promise to do my editorial best to hew excesses from the text — while simultaneously promising never to pass up a potential Meatloaf reference — readers ought nevertheless to prepare for the occasional indulgence when a point needs to be driven home…

- “Mishima has gone and actually done what these rightists only talk about. And it is not only the rightists who are stirred. Here in Japan, there must be thousands of frustrated people. They have no outlet for their pent-up feelings. Suddenly, along comes Mishima and his young followers of the Shield Society. They not only preach restoration of the emperor-centered values of traditional Japan, they try to do something about it.That kamikaze spirit still has appeal in this country. You may be a rightist, you may be a leftist, you may be quite non-ideological, but with a grudge against, say, your boss. Normally, you don’t do anything about your grudges or your frustrations, you hold them in. But when you read or hear about an act like Mishima’s – well, there is always the chance that you might want to go out and do the same.”

- “Ready to talk politics with your family over Thanksgiving dinner?—Let us first look briefly at the concept of seppuku.” “Before we go through with this romantic tryst—Let us first look briefly at the concept of seppuku.” “Moses, what have you brought us on those tablets of yours?—Let us first look briefly at the concept of seppuku.” It just doesn’t get old!

- We don’t have time here to debate this conclusion, which does not diminish the assertion: rather, our staff are too busy creating a show upon which this subject will be debated, after which they plan to sell the advertising rights to the highest bidder…