Scholars estimate that there are currently between five-hundred-eleven and seventy-two-thousand-nine-hundred-fourteen reasons to celebrate the life of Samuel Beckett, who was born on this day in 1906. I list below only a few, with no organizational reference to importance or meaning.

«»

It is likely that I have read the trilogy Molloy/Malone Dies/The Unnameable two times in my life. I do not remember exactly. It’s a big blur when I try to remember reading it, however many times that actually happened, the reading that is, although I also cannot count the number of times I’ve tried simply to remember reading it. Whatever the number of times I’ve read it, it’s likely that two is twice more than the number of times the average person needs to read these books.

I do not know how to provide a summary of these books; likely it’s unimportant. That there are plots-ish…, is for others to untangle. Let them. When I think about it I feel like I do after I’ve spun around in circles, dizzied, ready to fall over, slightly electric at the experience. Maybe the books are a spiral, and it’s possible someone exists with the time to spin to their innermost centers. After 414 very tightly spaced pages in the edition I own, these closing lines:

… it will be the silence, where I am, I don’t know, I’ll never know, in the silence you don’t know, you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.

«»

The dreary thing about certain existentialists is their insistence upon the generalizability of their worldview, a position that all too often sounds like: because I feel despair, you should also. To which we can all reply: mmmhhh, no thanks.

I do not think of Beckett as a propagandist; nevertheless, read one of his stories or watch one of his plays and you’ll know quite well how he felt about humanity’s place in the world.

It’s worth keeping in mind some history: throughout the early part of the 20th Century life was flourishing, the arts were alive, the sciences were expanding—in short, the rational undertaking of the Enlightenment was in full swing—and then Europe set itself on fire. Twice, in some twenty years. Beckett lived through both wars, saw the horror and carnage. That would tarnish even the shiniest outlook and sink the spirits inclined to rise.

Though Irish, Beckett lived most of his life in France, and during the second world war actively served in the French Resistance. This fact has always stuck with me, for it, like his art, which was prolific in both quantity and media, seems to balance out the darkness, or at least make it less one-sided.

I’m not suggesting he didn’t find life as empty as he seems to; yet the man who wrote the line—”They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more”—continued to create very beautiful pieces of art throughout his entire life. That we die appears inevitable; that meaning is difficult to substantiate is open to debate; that either thought is woeful depends largely upon your viewpoint; that Beckett gave birth to light, and that that light has gleamed for well more than an instant, is inarguable

«»

Terribly shy, most people who knew him described him as extremely kind. I think that is nice.

«»

It’s a curious thing, his perpetual paring down, his stripping away. Such was Beckett’s eventual movement in opposition to the all-consumingness of Joyce’s writing. Slowly he became very much like someone whittling a stick, a process which inevitably leads to nothing. All that remains is the knife, but at least there is not doubt about the ability to cut.

All of that might sound like a study of nothing, or the process of obtaining it, which likely sounds like nothing else, or perhaps nothing else sounds like it, or, if you’re Beckett, the suggestion that nothing is more real than nothing.

(And here you thought Seinfeld had explored the subject.)

Perhaps more circles? Or spirals? The difference between the two is registered only by the ability to stand in a position of measurement, which would be located right about…, no, not there. It’s further on. In the dark shadowy spot over there. Keep going down the way. You can’t see clearly?—Well don’t let that stop you. Keep going. And going. Yes, we know it’s dark but someone’s got to try and measure exactly how dark. What’s that you say?—It’s grown too silent to hear properly? You can’t go on, You’ll go on…

Say what you will, but that takes balls.

«»

Beckett’s almost as quotable as his fellow countryman Oscar Wilde, and six seconds of searching will get you pages of pith. I hesitate to pile on the quotes as I do not want to suggest that any one phrase could contain him, or anyone else. Yet there are few lines about creating more apt than the following:

Try again. Fail again. Fail better.

I wanted to write about Beckett last year on his birthday, but didn’t. Now I’ve done this here. It is; I don’t find it satisfactory and feel compelled to say: Sorry Sam. Maybe next year will be better.

«»

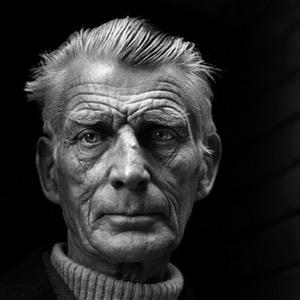

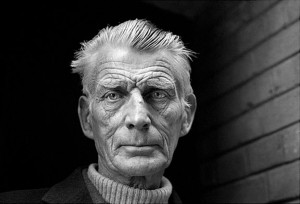

Lastly, and quite simply: what a face to look upon.